Adjunctive therapy consists of several approaches to inhibit pathomechanisms of severe sepsis.

This is a new recommendation since 2008 because a number of clinical studies have verified that formal screening protocols for sepsis improve outcome (Jones et al.JAMA. 2010;303:739-746; Moore et al. J Trauma. 2009;66:1539-1546).

The underlined sections are new to the 2012 guidelines as ample evidence now exists to recommend these, rather than simple suggestions. (Memel L, Maki D. Ann Intern Med.1993;119:270-272).

The underlined recommendation on antigen detection systems for candidemia is new. It is based upon a number of clinical studies in neutropenic patients and a meta-analysis that included some ICU patients showing these assays, despite suboptimal sensitivity and specificity, allow for significantly faster diagnosis of invasive candidiasis and earlier intervention with antifungal agents. Early therapy for candida sepsis improves outcome (Alam et al. BMC Infect Dis. 2007;7:103; Sendid et al. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2008;15:1868-1877).

![]()

This recommendation was not graded in the 2012 guidelines as it is based on clinical experience and expert opinion rather than specific clinical trials.

![]()

The 1-hour recommendation for severe sepsis without septic shock was ungraded in the 2008 guidelines as some additional studies have suggested early intervention is an important prognostic indicator even without shock. There are fewer data here than in patients with septic shock. The next slide provides a summary of the evidence. The remark was added to clarify that the guidelines subcommittee acknowledges that this is a goal that may be difficult, if not impossible, to fully implement in all healthcare settings, busy emergency departments, and mass casualty settings, but should be the goal where possible.

![]()

A summary of recent studies supporting broad-spectrum, empiric combination therapy in the early treatment of sepsis/septic shock.

Legend s-sepsis; ss-severe sepsis; SS-septic shock; HD-hospital discharge; ED-emergency department; or-odds ratio; ns-not significant; HR-hazard ratio; MVR-multivariate regression

1.Kumar et al. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:1589–1596

2.Barochia et al. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:668–678

3.Ferrer et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:861–866

4.Barie et al. Surg Infect. 2005;6:41–54

5.Levy et al. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:367–374

6.El Sohl et al. J Am Geriat Soc. 2008;56:272–278

7.Gurnani et al. Clin Ther. 2010;32:1285–1293

8.Nguyen et al. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:1105–1112

9.Castellanos-Ortega et al. Crit Care Med.2010;38:1036–1043

10.Gaieski et al. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:801-807

11.Larsen et al. Pediatrics. 2011;127: e1585–e1592

These underlined changes from the 2008 guidelines were added to acknowledge that viral pathogens (e.g., influenza, hemorrhagic fever viruses) can cause sepsis on occasion and that antibiotic choices need to consider the levels of antibiotics achievable at the site of infection (cerebrospinal fluid, intracellular spaces, when appropriate) [Smith et al. Crit Care Med.2010;38:41-51]. The de-escalation comment and the recommendation were upgraded to Grade 1B from the 2008 guidelines (Grade 1C) as evidence of reduced risk of antibiotic resistance can be accomplished by careful use and antibiotic stewardship to retain the activity of available antibiotics.

-

Gao F et al. Crit Care.2005;9:R764–R770

-

Schorr C. Crit Care Clin.2009;25:857–867

-

Girardis M et al. Crit Care.2009;13:R143

-

Pestaña D et al. J Trauma.2010;69:1282–1287

-

Berenholtz SM et al. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Safety.2007;33:559–568

-

Masterton RG. Crit Care Clin. 2011;27:149-162

![]()

This is a new recommendation in the 2012 guidelines. Procalcitonin (or other biomarkers) has been studied in a number of trials as a guide to discontinue potentially unnecessary empirical antibiotics when the clinical situation is stabilized. The available data suggest that this might be useful in saving money and reducing antibiotic use (Heyland DK et al. Crit Care Med.2011;39:1792-1799). However, the safety of this measure and the likelihood it can significantly reduce antibiotic resistance development of Clostridium difficile or other adverse events associated with continued antibiotic use remains to be demonstrated. Procalcitonin levels are not recommended as a biomarker for the diagnosis of sepsis.

![]()

We upgraded the recommendation for neutropenia and for Pseudomonas spp. severe sepsis to 2B from 2D in the 2008 guidelines and added other difficult to treat pathogens such as Acinetobacter spp. in the 2012 guidelines. It has been repeatedly demonstrated that empiric therapy that does not cover these pathogens that are later found to be the cause of the infection is associated with significantly worse outcomes. However, much of this clinical data is not based on ICU patients with septic shock, and this indirectness of the data leads us to make it a suggestion (Grade 2) rather than a Grade 1 recommendation. The next two slides provide further supportive evidence of the value of empiric combination antibiotics in treating septic shock to assure that the infecting microorganism that caused septic shock is treated (Kumar et al. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:1773-1785; Micek ST et al. Antimicrob Agents Chemother.2010;54:1742-1748).

Kumar et al. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:1773–1785.

Legend: HR-hazard ratio; CI-confidence interval; or-odds ratio.

Micek et al. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:1742–1748.

Legend: IIAT-inappropriate initial antimicrobial therapy, AOR-adjusted odds ratio, CI-confidence interval, APACHE-Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation.

Kumar et al. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:1651–1664

Garnacho-Montero et al. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:1888-1895

Legend: or-odds ratio; CI-confidence interval; VAP-ventilator-associated pneumonia; AHR-adjusted hazards ratio.

![]()

Al-Hasan et al. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:1386-1394.

Legend: GNB=Gram-negative bacteria, AHR-adjusted hazard ratio, CI-confidence interval.

![]()

Martinez et al. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:3590-3596

Rodriguez et al. Crit Care Med. 2007; 35:1493–1498

Legend: GNB-Gram-negative bacteria, or-odds ratio, CI-confidence interval, ESBL-extended-spectrum beta-lactamase, CAP-community-acquired pneumonia, HR-hazard ratio.

![]()

This recommendation relating to pneumococcal septic shock was added to the 2012 guidelines in keeping with a number of studies (see next slide for summary of evidence) suggesting improved outcomes for patients with septic shock when a macrolide is added to a beta-lactam in the early phase of treatment. The reasons for this apparent improved outcome in some, but not all, clinical studies are not clear but might relate to the anti-inflammatory actions attributable to macrolides or other mechanisms. It was decided to make this a suggestion until further clinical studies can support or refute this evidence.

![]()

The collective, observational clinical data support adding a macrolide to beta-lactams even in documented, bacteremic pneumococcal septic shock. The mechanism responsible for this apparent benefit is unclear but is generally attributable to the anti-inflammatory effects of macrolides. Combination therapy is a level 2 recommendation, despite the additional expense and concern over possible promotion of macrolide antibiotic resistance by its widespread, potentially unnecessary use for this indication. Further study and mechanistic evidence to support its use is clearly needed to support combination treatment over standard beta-lactam monotherapy.

Legend: PSI-pneumonia severity index, B-bacteremia, S-sepsis, MV-mechanical ventilation, ns-not significant.

-

Martinez et al. Clin Infect Dis.2003;36:389-395

-

Baddour et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med.2004;170:440-444

-

Weiss et al. Can Respir J.2004;11:589-593

-

Rodriguez et al. Crit Care Med.2007;35:1493–1498

-

Lodise et al. Antimicrob Agents Chemother.2007;51:3977-3982

-

Chokshi et al. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis.2007;26:447-451

-

Martin-Loesches et al. Intensive Care Med.2010;36:612–620

The grade was increased from 2D in 2008 to 2B in 2012 as some new clinical data on early de-escalation of antibiotics suggest that this can be done safely. Exceptions exist to rapid conversion to monotherapy as indicated. Useful references include:

-

Schorr C. Crit Care Clin.2009;25:857–867

-

Girardis M. Crit Care.2009;13:R143

-

Pestaña D. J Trauma.2010;69:1282–1287

-

Berenholtz SM. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf.2007;33:559–568

-

Black MD. Crit Care Med.2012;40:1324–1328

-

Masterton RG. Crit CareClin.201;27:149-162

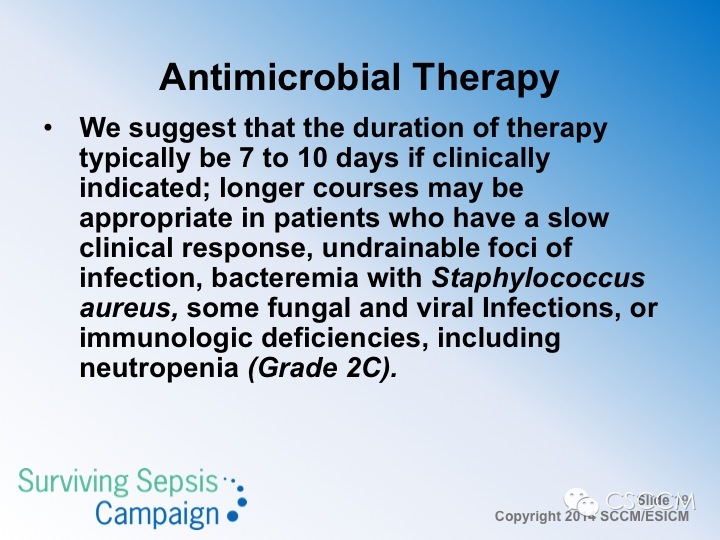

The 2008 guidelines did not contain this recommendation. The committee wanted to clarify that certain specific indications for antibiotic therapy require more prolonged therapy than 7 to 10 days to avoid antibiotic failures and relapsing infections. Some of those situations are listed here and are provided as suggestions rather recommendations (Grade 2C).

![]()

These are new guideline statements following the events of the 2009 influenza pandemic when evidence rapidly accrued that early institution with antiviral therapy could be lifesaving in severe influenza. The second point was added to point out that antibiotics should be stopped as soon as possible after it is determined that an infectious disease is not causing the acute inflammatory state that was suspected to be due to sepsis. Preserving antibiotics until their use is warranted is important in ICU care and in medical care in general as part of antibiotic stewardship programs.

![]()

These recommendations and grade guidelines are comparable to those of 2008 except the time interval was lengthened for practical reasons to 12 hours versus the original 6-hour period.

![]()

These recommendations were not graded as they were in the 2008 guidelines as they are primarily based upon common sense clinical observations and expert opinion rather than high-level clinical study evidence.

![]()

The 2008 guidelines did not make a selective digestive decontamination recommendation. Despite the ongoing controversy over its efficacy and impact on antibiotic resistance patterns, the committee agreed that it should be graded as much evidence now exists in the medical literature about this topic. We believe that this work deserves to be tested in long-term follow-up studies to determine its appropriate place in sepsis care in different regions of the world. Useful references include:

-

Liberati A et al.Cochrane Collaboration. 2010;9:1–72

-

de Jonge E et al. Lancet.2003;362:1011–1016

-

de Smet et al. N Engl J Med.2009;360:20–31

-

Cuthbertson BH et al. Trials.2010;11:117-120

-

de Smet AMGA et al.Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11:372–380

-

Oostdijk EAN et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med.2010;181:452–457

-

Ochoa-Ardila MEet al. Intensive Care Med.2011;37:1458–1465

![]()

Routine infection control practices in the ICU are important, and recent guidelines on this topic have been published (Aitken et al. Crit Care Med.2011;39:1800-1818). Despite rather convincing and detailed meta-analysis of the value of SDD, SOD and oral rises with CHG (see SSC supplemental digital file 3), the practice remains variably applied and is a subject of ongoing controversy. oral CHG is often preferred based upon its ease of administration, safety, and the relative lack of concern over promoting antibiotic resistance within ICUs that widely use this practice. The existing evidence indicates that the use of SDD does not appear to be a major factor in promoting resistance in the ICU microbial flora. Three recent studies have studied this question. One suggested it does increase resistance to therapeutic antibacterials, one found no evidence of increased resistance with the use of SDD, and a third study found that the frequency of antibacterial resistance was actually reduced after the introduction of widespread use of SDD:

-

de Smet AM et al. Lancet Infect Dis.2011;11:372-380

-

Oostdijk et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med.2010;181:452-457

-

Ochoa-Ardila et al. Intensive Care Med2011;37:1457-1465

Clearly this question needs to be answered with additional long-term studies to verify the safety and efficacy of this method of infection prevention. Until such time as this information becomes available, a weak level 2 recommendation is given in support of SDD or its variants in regions with experience in its use.